Thirty years ago, a breakthrough technology was poised to transform how people stayed informed, entertained themselves, and maybe even shopped. I’m not talking about the World Wide Web. True, it was already getting good buzz among early adopter types. But even three years after going online, Tim Berners-Lee’s creation was “still relatively slow and crude” and “limited to perhaps two million Internet users who have the proper software to gain access to it,” wrote The New York Times’ Peter H. Lewis in November 1994.

At the time, it was the CD-ROM that had captured the imagination of consumers and the entire publishing industry. The high-capacity optical discs enabled mass distribution of multimedia for the first time, giving software developers the ability to create new kinds of experiences. Some of the largest companies in America saw them as media’s next frontier, as did throngs of startups. In terms of pure mindshare, 1994 might have been the year of Peak CD, with 17.5 million CD-ROM drives and $590 million in discs sold, according to research firms Dataquest and Link Resources.

You already know that the frenzy didn’t last. As the web got faster, slicker, and more readily accessible, CD-ROMs came to look pretty mundane, and eventually faded from memory. Myst, once the best-selling PC game of all time, might be the only 1990s disc that retains a prominent spot in our shared cultural consciousness. (Full disclosure: I do have a friend who can be relied upon to fondly bring up Microsoft’s Cinemania movie guide about once a year for no apparent reason.)

This story is part of 1994 Week, where we’ll revisit some of the most interesting and confounding developments in tech 30 years ago.

Revisiting the discs that defined the mid-1990s—all of which are incompatible with modern operating systems—isn’t easy. To get some of them up and running again, I downloaded virtual CD-ROM files from the Internet Archive and used them with Windows 3.1 on my iPad Pro, courtesy of a piece of software Apple removed from the App Store in 2021. Spending time with titles such as Compton’s Interactive Encyclopedia and It’s a Wonderful Life Multi-Media Edition, three decades after they last commanded my attention, was a Proustian rush.

You may not want to go to similar extremes. But would you indulge me as I wallow in enough CD-ROM nostalgia to get it out of my system?

Multimedia on demand

1994’s CD-ROM boom had been more than a decade in the making. In 1983, Sony and Philips established the technical standard as a spinoff of the then-new audio CD. The “ROM” stood for “Read Only Memory,” indicating that the data on a disc couldn’t be changed. That was a fundamental limitation compared to a hard drive or floppy disc. But as originally specified, one CD-ROM could store 550 MB of data, a mind-melting capacity in the mid-1980s, when even a 20 MB hard drive felt sinfully luxurious and floppies maxed out at 1.2 MB. “It’s 50 feet of bookshelves on one little disc,” explained a Philips executive. (Later CD-ROMs settled on a capacity of 680 MB.)

Among the technology’s earliest champions was Microsoft, best known as the purveyor of the industry’s dominant operating system, MS-DOS (and, starting in 1985, a graphical user interface known as Windows). In 1986, the company published a book with the portentous title CD-ROM: The New Papyrus. In the introduction, cofounder Bill Gates explained why the future of storage was optical:

A floppy disk can store only 5 real-life images, but a single CD can store 5000 such images. The floppy can store only 3 seconds of high-quality audio, but the CD can store an hour. It’s this remarkable power of the CD ROM disc to digitally store video images, audio, data, and computer code in any combination that underscores its vast potential.

In a few years, after the CD ROM becomes commonplace, anyone looking back at the information, education, or entertainment applications of today will understand the limited appeal they had. The combination of a CD ROM with a microcomputer creates a medium that potentially is more interactive than any previous consumer product. We believe this interaction will result in a product that will stimulate and enrich a person in a manner that is far superior to passive systems such as television.

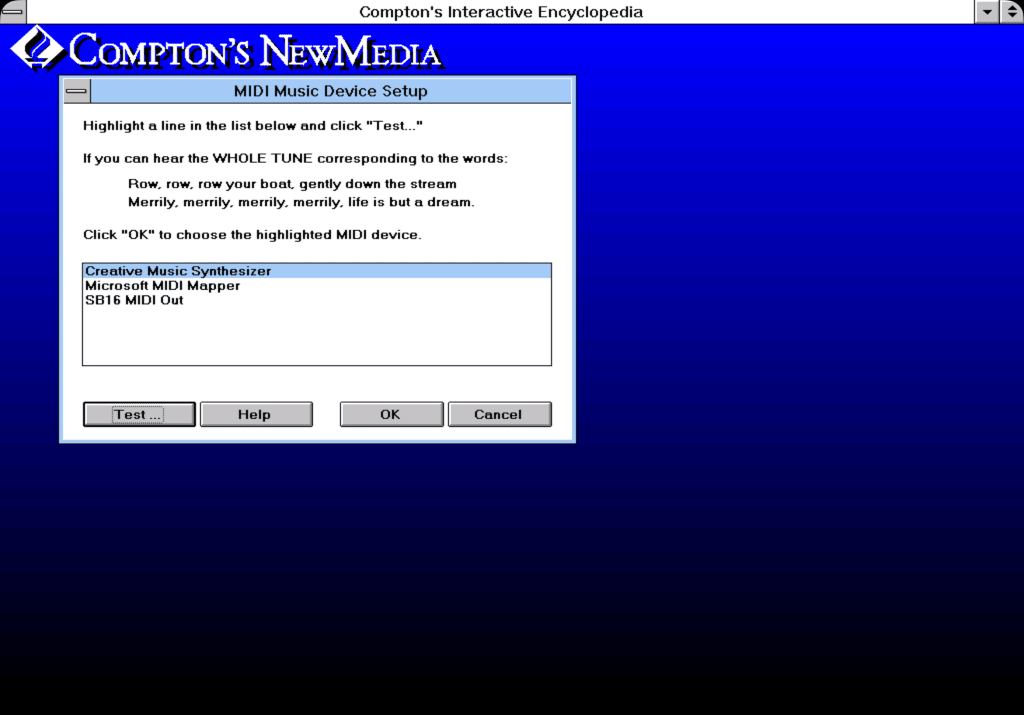

When Gates wrote that, CD-ROM’s potential to store vast quantities of photos, audio, and video was almost moot. They wouldn’t have been able to be reproduced by typical MS-DOS PCs, which offered rudimentary graphics and sound capabilities at best. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that Windows caught on, graphics got fancier, and audio cards such as the Sound Blaster became common. In 1991, an industry consortium called the Multimedia PC Marketing Council formalized a concept called the “Multimedia PC”—a Windows 3.0 machine with at least a 16-MHz 386SX processor, 256-color graphics at 640-by-480 resolution, 8-bit sound, and a CD-ROM drive.

As 1994 approached, MPCs were popular enough that publishers of CD-ROM software finally had a critical mass of customers. The Software Publishers Association reported that CD-ROM software sales in the last quarter of 1993 totaled $102 million, more than the total for the first three quarters combined. “For investors and entrepreneurs who have held out hope the hype surrounding the multimedia discs would someday become reality, the numbers are proof the promise of CD-ROM has finally arrived,” wrote the Los Angeles Times’ Amy Harmon. In The New York Times, reporter Steve Lohr quoted an analyst firm’s estimate that 35 percent of PCs would come with a drive in 1994, up from 2% in 1992.

After talking up CD-ROMs for years, Microsoft had launched a whole “Microsoft Home” division centered around them. Its ambitious offerings included Encarta (an encyclopedia), Explorapedia (an encyclopedia for kids), Microsoft Bookshelf (a dictionary, thesaurus, and other reference works). Microsoft Complete Baseball (stats), Cinemania (movie reviews from Roger Ebert, Leonard Maltin, and others), Art Gallery (reproductions of 2,000 works), Gahan Wilson’s The Ultimate Haunted House (a game created by the celebrated cartoonist), and others. Along with being sold at computer shops and bookstores, the company’s discs were often bundled with MPCs and add-on CD-ROM drives.

Other big names entered the field as well, if not so expansively. Apple, for instance, announced plans to work with CBS and The New York Times on a CD-ROM history of the Vietnam War. And the oldest-school tech giant of them all, IBM, found the strangest of bedfellows in Playboy magazine, whose famous interviews it collected on disc.

The field also attracted the attention of print publishing’s behemoths. In 1993, newspaper titan The Tribune Co. acquired Compton’s NewMedia, which had released its first encyclopedia on a disc in 1989—and claimed, briefly, that a patent it held entitled it to a licensing fee from everyone else in the business. Famous paper periodicals such as Time, Newsweek, and PC Magazine issued CD-ROM editions, although they could be a tough sell: As one Newsweek executive lamented, newsstand browsers couldn’t rifle through a disc before deciding to buy it.

In the end, the vast majority of 1994’s CD-ROMs were produced by tiny multimedia studios, 20,000 of which had been founded worldwide, estimated Dataquest. Most made very little money, but expectations of future success ran high, with the Los Angeles Times reporting on the “grudge match” between LA and San Francisco to dominate “an industry destined to shape the economy of California for decades to come.”

Well before tech workers at companies such as Twitter, Uber, and Dropbox took over San Francisco, the hipster CD-ROM artisan became an archetypal character associated with the city. As Linda Jacobson, an editor at Computer Life magazine, explained in a September 1994 New York Times article, “Here in San Francisco, everyone is working on a multimedia title.” As they set up shop, a chunk of the South of Market neighborhood, formerly a drab expanse of warehouses and printing plants, became known for a time as “Multimedia Gulch.”

What emerged from these CD-ROM startups tended to be way quirkier than anything produced by the likes of Microsoft or Time. Consider Blender and Substance Digizine, two CD-ROM magazines that debuted in 1994 and were aimed, according to Entertainment Weekly’s Ty Burr, at “the hard-moshin’ Gen X crowd.” Unlike a copy of Rolling Stone, they could perform nifty tricks such as playing music rather than merely reviewing it. But they were also ignorant of best practices about consistent navigation and clean text presentation—many of which hadn’t been invented yet—and limited by the screen resolution and colors then available. The results were ugly and impenetrable in ways their print counterparts were not. (Tedium’s Ernie Smith has a good look at the whole phenomenon of magazines on disc and why it didn’t work.)

CD-ROM proved especially irresistible to game publishers, which had long been constrained by the skimpy capacity of floppy disks. Brøderbund‘s Myst, created by brothers Rand and Robyn Miller, arrived for Windows PCs in February 1994 after a 1993 Mac release. With 2,500 frames of 3D imagery and 40 minutes of music, the enigmatic puzzle/adventure game would have required 500 floppies. Another boundary-pushing 1994 release, Access’s Under a Killing Moon, was a sci-fi thriller so dense with content—including cut scenes starring big-name actors Brian Keith, Margot Kidder, and James Earl Jones—that it came on four CD-ROMs.

More mundane applications also abounded. Several companies saw CD-ROM as a way to revolutionize shopping, including Canada’s Magellan, which released a disc with digital replicas of 24 mail-order catalogs from merchants such as Land’s End, Brooks Brothers, and Spiegel. You still had to dial an 800 number to buy anything, but at least the dead-tree versions of the catalogs wouldn’t pile up.

Assessing the discs

More or less by accident, I spent most of 1994 swimming in CD-ROMs. On a morning in late January, the computer magazine where I worked folded and laid off the entire staff. Suddenly needing paid work, I began lining up freelance assignments that afternoon. My steadiest market was Multimedia World, one of several publications founded to cover CD-ROM and related matters. Reviewing discs for fifty cents a word helped keep me housed and fed until I found another staff job late that year.

Tragically, I didn’t carefully file away all the Multimedia World issues with my reviews. I did, however, manage to hold onto unedited Microsoft Word drafts of a few of them. These opening paragraphs will give you a taste of both my enthusiasm for the new medium and its sheer diversity of subject matter:

Just as I’m finally replacing all my vinyl albums with compact discs, I’m faced with the prospect of a whole new media for recorded media—and I couldn’t be happier. Ebook’s new Jazz Portraits discs offer a whole new way to appreciate one of America’s great native artforms.

H.R. “Bob” Haldeman—Richard Nixon’s steely chief of staff—was called a lot of things in his day, but who would have expected that “multimedia pioneer” would one day be one of them? Yet that’s an honor that he has richly earned with the publication of Sony ImageSoft’s The Haldeman Diaries: Inside the Nixon White House.

Confession time: when I think of It’s a Wonderful Life, what it’s usually brought to mind has been all the Christmas Eves I’ve spent channel surfing in futile attempts to find something—anything—else to watch on TV. But I’ve just experienced Kinesoft’s It’s a Wonderful Life Multi-Media Edition, and I feel like I’ve discovered a classic American film for the first time.

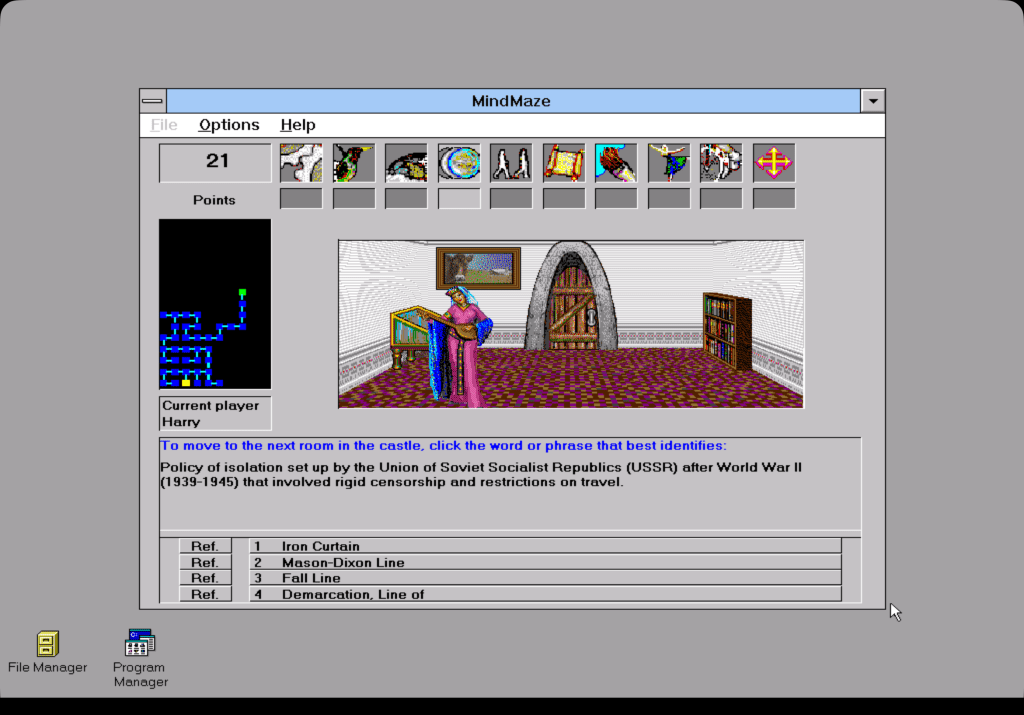

Evaluating multimedia encyclopedias turned out to be practically a part-time job in itself, an opportunity I relished in part because my father had reviewed (and trashed) a new edition of the dead-tree Encylopaedia Britannica when I was a kid. In 1994, I wrote a roundup review covering three of them—Encarta, Compton’s Interactive Encyclopedia, and the Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia. Then I followed up in 1995 with a sequel that also included the Britannica (a latecomer to the medium) and something called Infopedia.

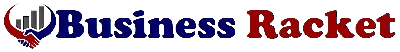

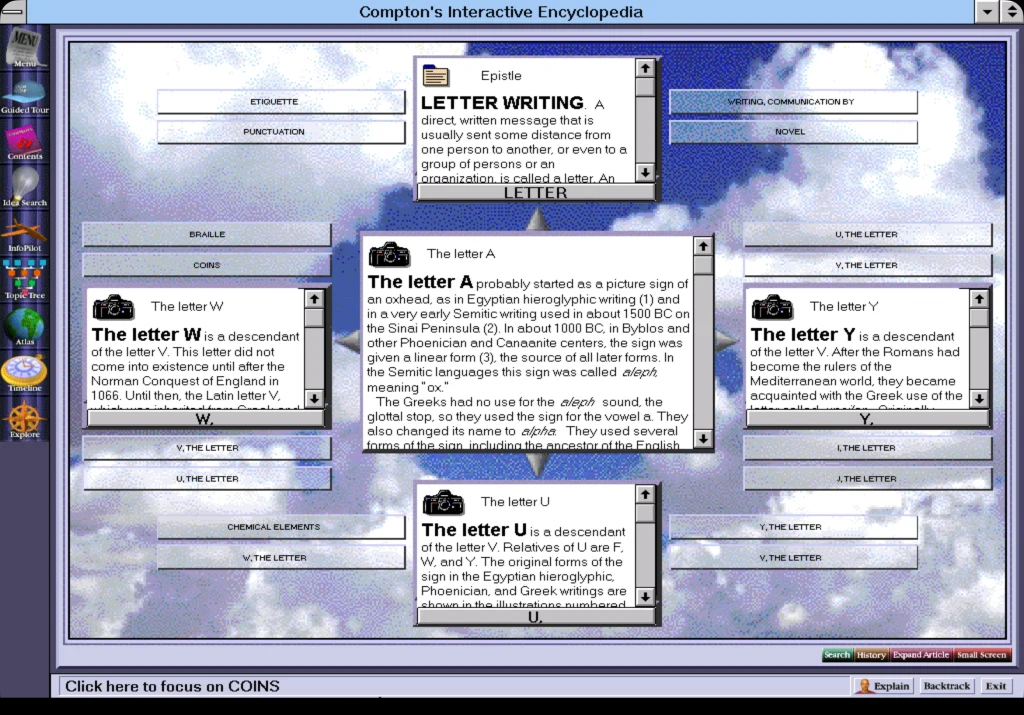

Returning to some of those titles as I worked on this article reminded me how big a challenge their creators had taken on. At the time, nobody had definitively figured out how to facilitate searching and browsing massive amounts of information on a PC. Every encyclopedia tried several different approaches, most of them shockingly clumsy by 2024 standards. Encarta had a six-step Find Wizard, plus a separate tool for pulling up photos, audio, video, maps, and charts; Compton’s options included the InfoPilot, which slathered as many windows and buttons as possible on top of a backdrop depicting clouds in the sky.

I’d also forgotten how quickly CD-ROM publishers started maxing out the discs’ capacity. I still have my vintage notes from a 1994 interview in which Microsoft product manager Kathleen Fiander told me the company had based most of Encarta’s 9 million words of text on Funk & Wagnalls’ print encyclopedia for space-saving reasons: “People ask us why we chose them, and it’s because they have a very terse, concise encyclopedia, which made it very adaptable to CD ROM.”

In the age of Wikipedia—which has 500 times more text—material that dazzled me in 1994 barely registers as useful. For example, that year’s Encarta gave Ansel Adams only two paragraphs, with no examples of his work. Appreciating CD-ROM’s importance requires remembering what the principal competition was at the time: not the entire internet, but going to the library. Or maybe just staying uninformed.

Of course, CD-ROM did compete with the internet soon enough. But long before it definitively lost that battle, there were signs it wasn’t living up to some of the more exuberant expectations it had inspired. Just how much appetite PC users had for buying discs on an ongoing basis had always been an open question. In August 1994, for instance, an article by the Los Angeles Daily News’s Walter Hamilton contended that many people lost interest in the medium after “fooling around with an encyclopedia and a couple of games.” Cost was presumably one factor: Microsoft’s Fiander had told me that Encarta’s $139 price was a major selling point compared to a $1,500 print encyclopedia, but it was still a lot of money.

”[F]or all the potential of the medium,” even its most fervent proselytizers concede that no one has managed to come up with a title that quite lives up to it,” wrote The Los Angeles Times’ Amy Harmon in September 1994. “Developers compare the state of their craft to the early days of the nickelodeon, when movies were silent, scratchy, black-and-white, and not terribly creative.”

Shovelware, kitchen sink titles, just plain crap

Over time, CD-ROM publishers who made a good-faith effort to explore the medium’s potential may have been outnumbered by those with less lofty aspirations. Among the biggest players was SoftKey International, whose president, Kevin O’Leary—later better known as Shark Tank’s “Mr. Wonderful”—had gotten his start in the cat food business and treated software as a similar exercise in moving packaged goods. SoftKey’s products were available in 15,000 retail outlets and included five of North America’s top ten best-selling CD-ROMs. “It’s not about technology anymore,” O’Leary helpfully informed The Christian Science Monitor in May 1994. “It’s about marketing, merchandising, brand management, and shelf space.”

Across the industry, many discs were filled with, well, filler. “Call it ‘shovelware,’ or ‘kitchen sink’ titles, or just plain ‘crap,’ but the CD-ROM market is spiraling out of control with far too many pieces of plastic that would have been better off if manufactured into two-liter bottles or laundry soap containers,” groused the Oakland Tribune’s Howard Bryant in December 1994. Mediocrity became so prevalent that Wired ran a recurring feature on “CD-ROMs That Suck.” ESPN Sports Shorts, for example, featured “slide shows of anonymous sports figures in unnamed competitions, brief video clips of guys stealing bases and sailboats coming about, sound clips from announcers who are terribly excited about something, and so on,” wrote Robert Rossney. “It’s like watching TV a half-second at a time.”

Meanwhile, the online age was arriving—just at a leisurely pace. A May 1994 study from the Times Mirror Center (later known as the Pew Research Center) reported that only 12 percent of American households had a computer with a modem. Those that did dialed into bulletin-board systems and commercial services such as AOL and CompuServe; the consumer internet was so nascent that the study didn’t mention it. An October 1995 follow-up study found that only 3 percent of Americans used the World Wide Web. According to Pew, another five years elapsed before the majority of American adults were on the internet and eight more before most households had broadband.

Even as the internet played an ever-more important role in our lives, multimedia discs would continue to be produced, sold, and bought. (Encarta made it all the way to a 2009 edition.) For years, CD-ROM drives, and then DVD-ROM ones, remained essential equipment for installing humongous pieces of software such as operating systems and office suites—and were even handier when they gained the ability to burn discs. It’s just that nobody considered the technology to be cool or futuristic, or bothered to write any eulogies when it stopped mattering.

In retrospect, the CD-ROMs of 1994 were less a bold step forward than the last gasp of old, largely passive one-way media. Burrowing through their multimedia riches was great fun at the time. But the internet’s killer app would turn out to be engaging with other human beings. And spending a few hours in an AOL chat room would have told you far more about what was to come.