Want more housing stories from Lance Lambert’s ResiClub in your inbox? Subscribe to the free, daily ResiClub newsletter.

During the Pandemic Housing Boom, housing demand surged rapidly amid ultra-low interest rates, stimulus, and the remote work boom. Federal Reserve researchers estimate “new construction would have had to increase by roughly 300% to absorb the pandemic-era surge in demand.” Unlike housing demand, housing supply isn’t as elastic and can’t quickly ramp up. As a result, the heightened demand drained the market of active inventory, causing prices to overheat, with U.S. home prices in May 2024 a staggering 50.3% above March 2020 levels.

That overheated home price growth—coupled with the ensuing mortgage rate shock, with the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate jumping up from the all-time low of 2.65% in January 2021 to 6.49% as of this week—has created the fastest-ever deterioration in housing affordability.

On Friday, Vice President Kamala Harris unveiled her plan for addressing crushed housing affordability and spurring the construction of 3 million additional housing units in her first term as president, including:

- Federal assistance for first-time homebuyers: The Harris campaign says its plan would allow “over 4 million first-time buyers over four years to get significant down payment assistance on average of $25,000.”

- Creating a tax incentive to encourage builders to build starter homes: It would “complement” the Neighborhood Homes Tax Credit, the Harris campaign says.

- An expansion of existing tax incentives “for builders that build rental housing that is affordable”

- Creating a $40 billion innovation fund that would “empower local governments to fund local solutions to build housing”

The problem for Harris?

As the country saw firsthand during the Pandemic Housing Boom, housing demand can jump quickly, but total housing stock cannot respond as swiftly. So even if we assume that Harris’s plan could increase new construction to some degree, it would be a gradual increase that would take years to materialize. Meanwhile, the increase in housing demand from the $25,000 first-time down payment assistance would be felt immediately once it went into effect.

Giving millions of first-time homebuyers $25,000 down payment assistance could quickly ramp up housing demand, accelerate home price appreciation, and further deteriorate housing affordability, especially in Midwest, Northeast, and California housing markets where active housing inventory for sale remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

On the supply side, most housing analysts agree with Harris that the U.S. housing market needs more homes.

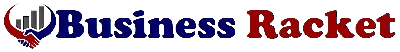

“Over the last several years, our research on the housing supply deficit has been widely followed, and while we’ve seen housing inventory improve slightly, a substantial undersupply still exists and remains one of the most significant obstacles facing the housing market today,” Len Kiefer, deputy chief economist at Freddie Mac, told ResiClub in May.

Just to bring housing vacancy rates back to historic norms, the U.S. housing market would need 1.5 million housing units built and sitting empty, according to research published by Freddie Mac economists in May.

So even by the most conservative accounting, Freddie Mac economists estimate the U.S. housing market is short 1.5 million homes. The actual housing shortage, Freddie Mac tells ResiClub, is around 3.8 million units.

This presents another problem for Harris: Not only would cash handouts accelerate housing demand faster than housing supply, but the realities of supply capacity would also be a significant roadblock to her goal of adding 3 million additional homes beyond the current trajectory during her sought-after four-year term.

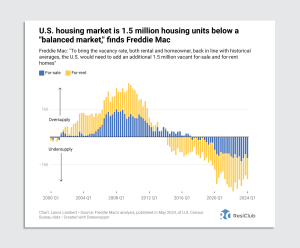

Since January 2020, the U.S. has completed an average of 1.39 million housing units per year. To achieve 3 million additional housing units beyond the current trajectory, annual housing starts would need to increase by 750,000, reaching 2.14 million starts per year in 2025, 2026, 2027, and 2028.

Such a significant increase in residential construction within a short timeframe, outside of a post-recession recovery, is unprecedented. Housing construction involves a massive number of inputs from around the world—such as lumber, windows, and concrete—which makes it challenging to achieve even a gradual increase in building capacity. During the Pandemic Housing Boom, builders attempted to quickly ramp up capacity to meet elevated housing demand. However, they managed to reach only 1.82 million annualized housing starts in April 2022 before hitting supply limits and facing skyrocketing input prices, including lumber, which at one point increased by more than 300%.

What can the U.S. do to improve housing affordability? First, simply give it time and make smart fiscal and monetary decisions. If you do that right, over time incomes rise and mortgage rates fall, helping to alleviate the historic housing affordability strain created by the accelerated pandemic housing demand boom and the ensuing rate shock. Second, focus on policies that increase housing construction and supply capacity—perhaps some of Harris’s current ideas—but without causing a sharp acceleration in demand.

One final point: The uncomfortable truth is that improving housing affordability might not be as easy or straightforward as some think. But just like with a Lego structure, sometimes it’s easier to identify what might break it (for housing, increasing homebuyer demand subsidies) than to fix it.